God's Gift to Fine Art: An Interview with Marvin Espy

This interview was conducted by Jake Perkins. It was lightly edited for length and clarity.

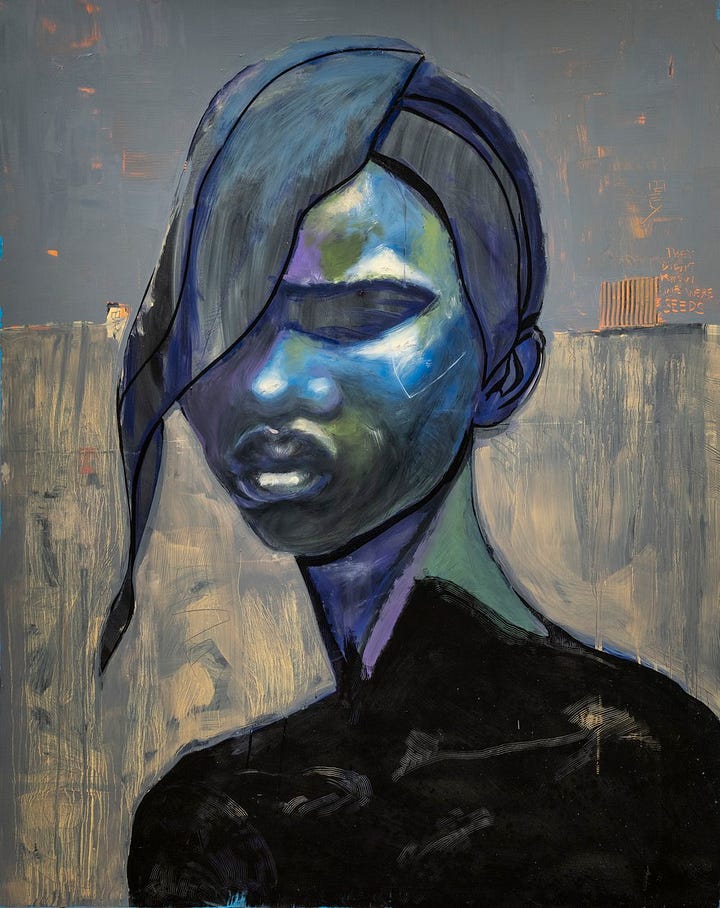

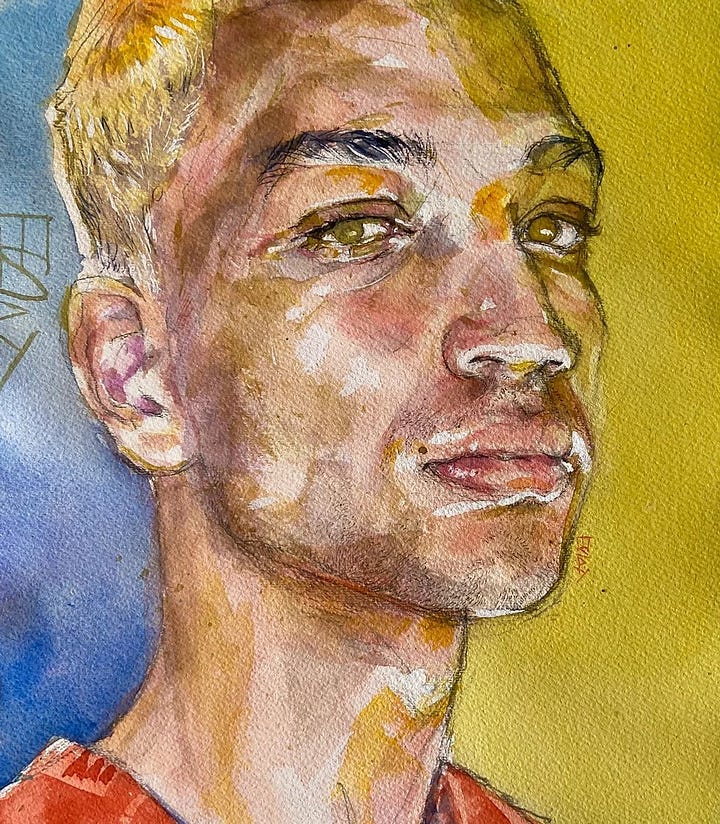

Marvin Espy is a remarkable multidisciplinary artist with many accolades. His mastery of color theory distinguishes his work. He incorporates this prowess by creating extraordinarily intricate portraits with unconventional colors that come together in beautifully curated collections.

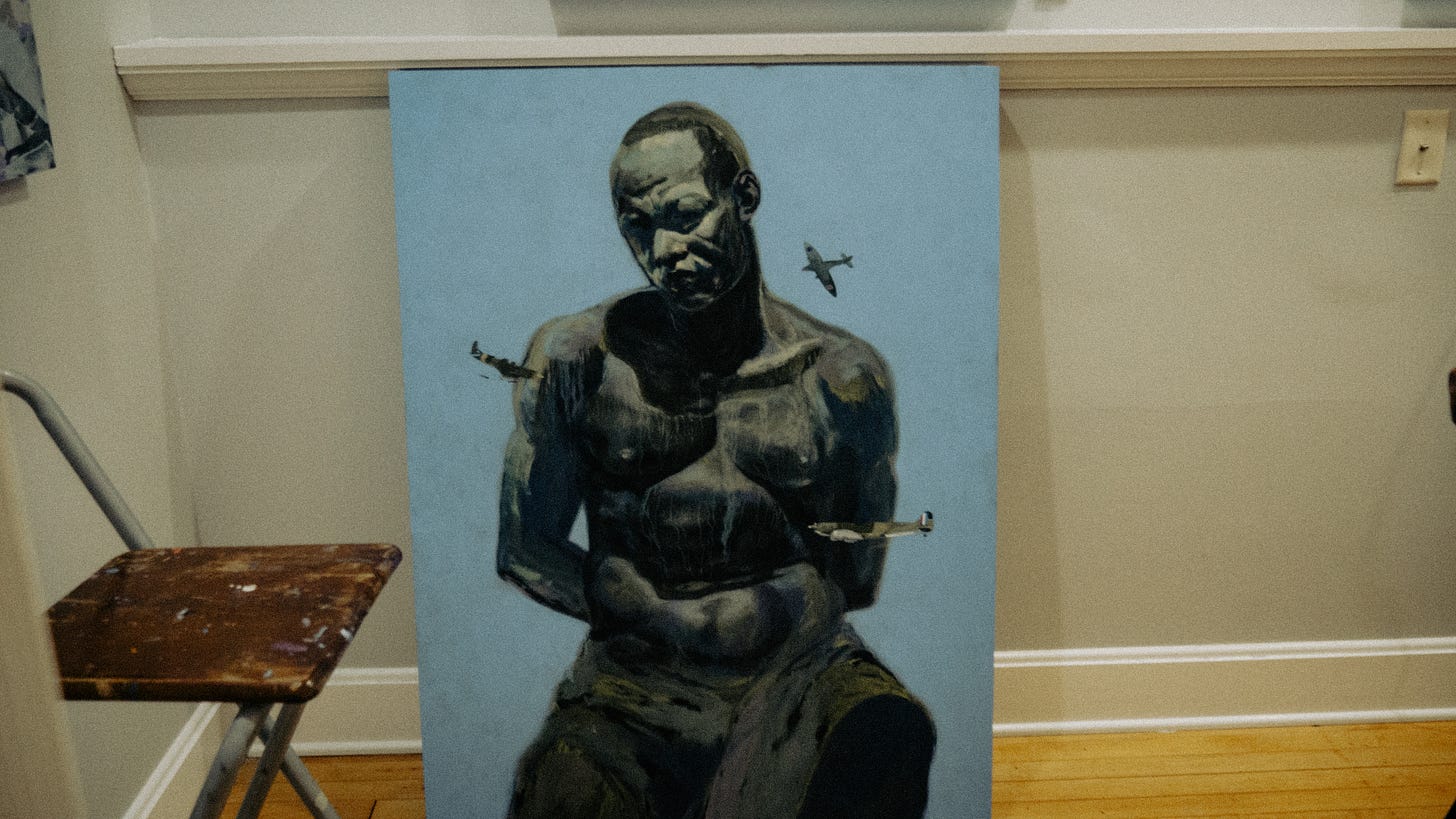

Espy invited me to meet him privately at his gallery, where I conducted this interview. We discussed his inspirations and motivators, including his goals in creating his "Context" collection, which aimed to depict Black and Brown people in unconventional contexts. We also discussed his art's religious, emotional, and societal motivations, including his response to the George Floyd incident in his "Up from the Asphalt" collection. The questions I asked are indented and displayed in bold.

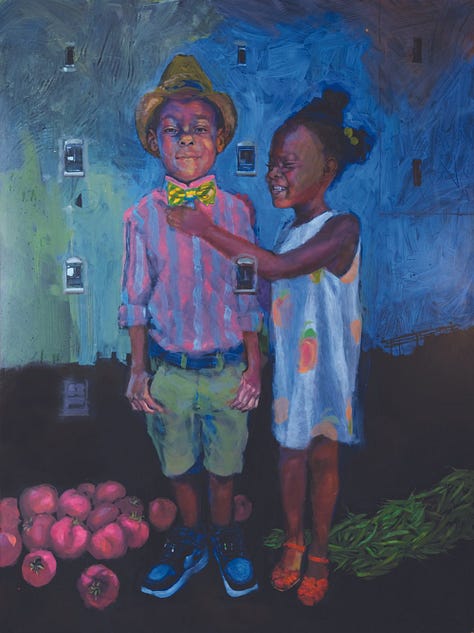

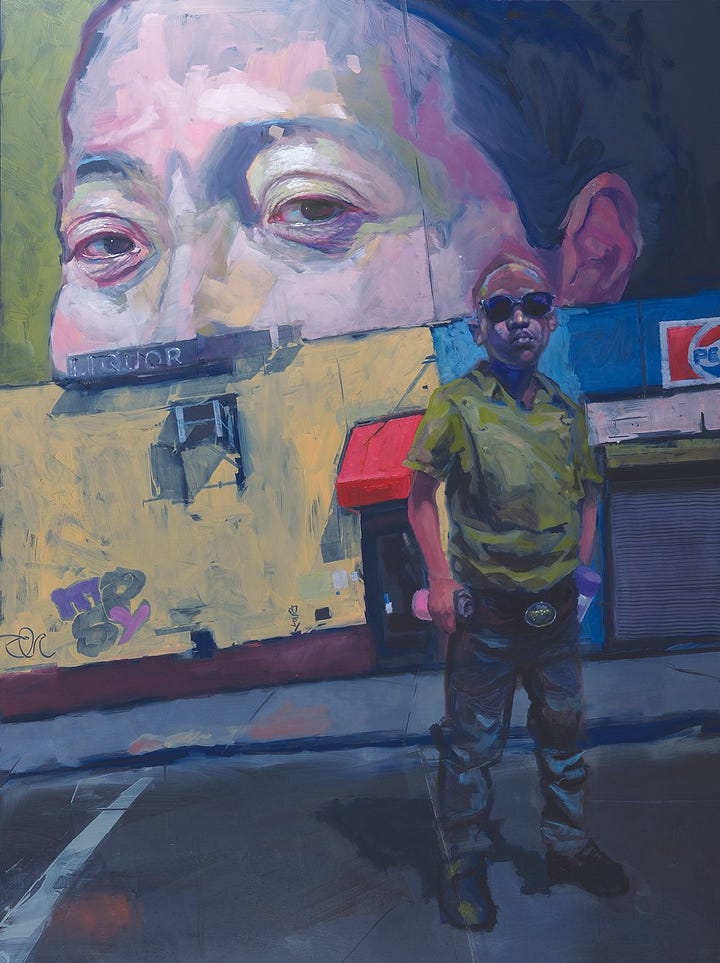

Espy: These [paintings] are from a series called “Context,” where I represented Black and Brown people in a context that we don’t normally see Black and Brown people. Traditionally, in art, especially American art history, we would see only a handful of themes in Black art. So you might be familiar with some of them, figures out in the hot sun bent over in a cotton field or a tobacco field or with harvesting equipment, that kind of thing. Or we could see an old man on a wooden porch, the front porch of a shaft.

Espy: You see those kinds of images often. Then there’s always the barbershop scenes or the woman braiding her child’s hair. Those stories have been told over and over again.

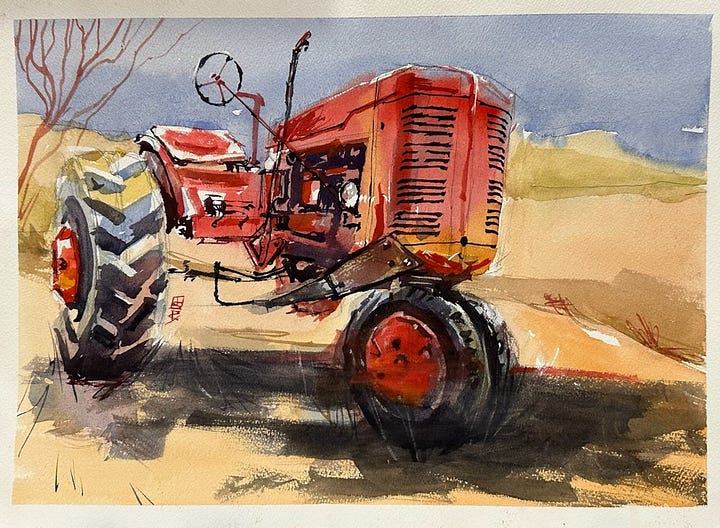

Espy: In “Context,” I was looking to show Black and Brown people in a context that we may not be as familiar with. This one came after the “Context” series, but it’s similar. I kept with the same theme.

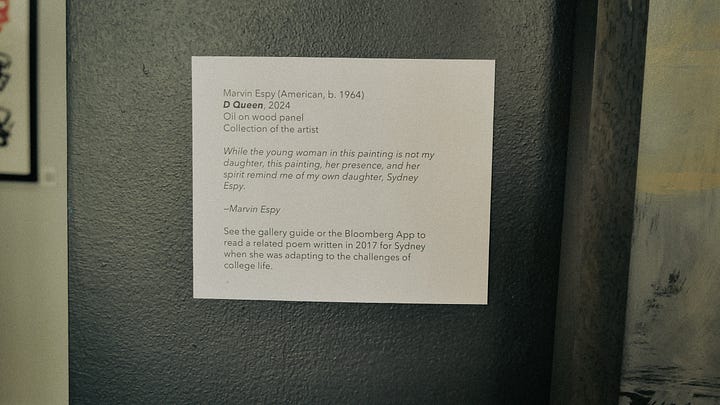

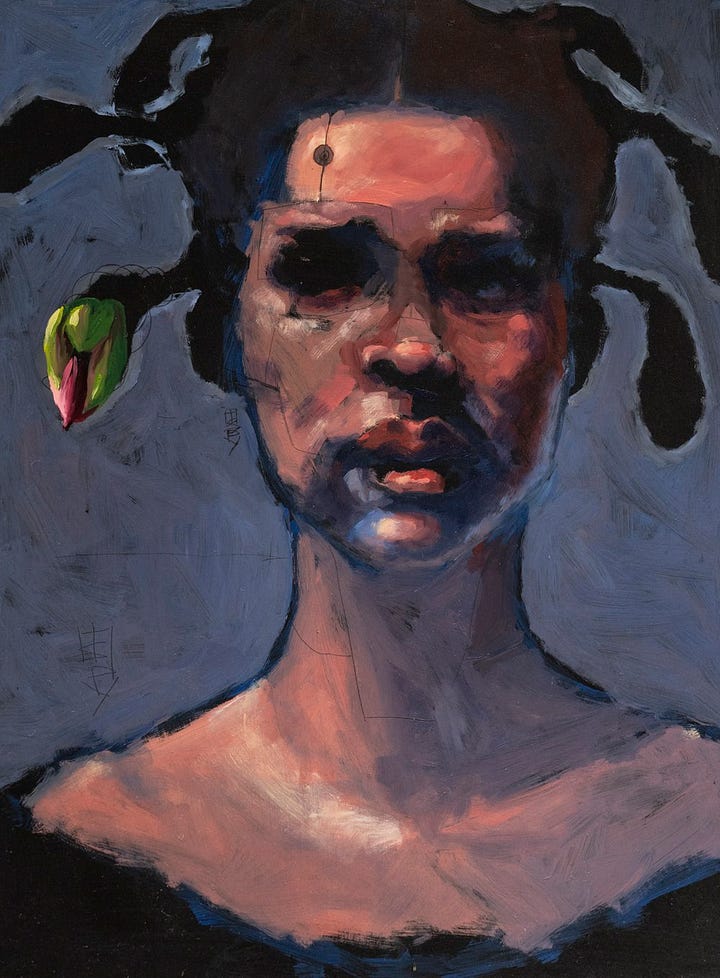

Espy: This is Evelyn. The whole time I had known her, she wore her hair in two cornrows. One day, she came to church, and it was in full bloom, right? She looked beautiful, confident, and proud. So she let me take a photo. As I was painting, I was still thinking about the “Context” exhibition. I wasn’t sure what I wanted to say about this painting, but I realized her experience in America, as a Black American, is of a mixed-race family. So I reached out to her and asked, “Hey, I got an idea. What do you think?”

Espy: Her afro and the brown hair on her light brown skin reminded me of a Dairy Queen cone dipped in chocolate. I said, “That ain’t offensive. Is it?” She goes, “I love it.” So I said, “You’re going to be the Dairy Queen.” The Dairy Queen marquee on the top and then the ice cream cone on the side were representative of her mixed heritage.

Do you think intersectionality played a part in this painting? You know, your perspective of Evelyn as a mixed woman and your perspective [of America] as a darker-skinned man.

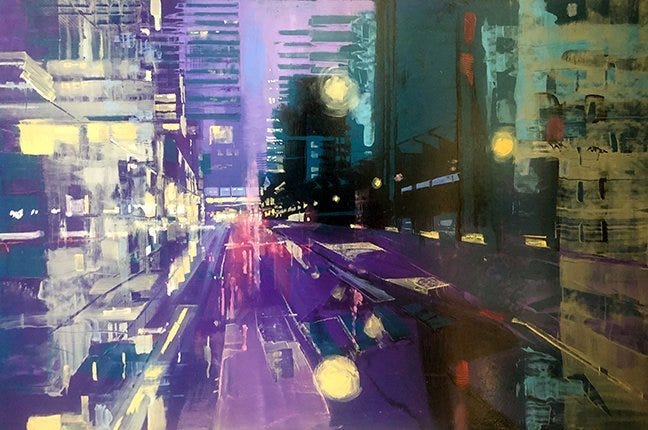

Espy: When she walked into church that day, it reminded me of my childhood because I was born in 1964. So my earliest childhood memories are from the seventies, and in the seventies, your sisters, your aunties, everybody had afros. So when she had that afro, it just felt like she would be a cousin of mine or, you know, part of my childhood, which is one of the reasons why I chose that background. I superimposed the Dairy Queen, but the background that I put there is from a scene from my hometown of Cincinnati. So, all of it feels like my childhood.

What did growing up in Cincinnati look like?

Espy: My family initially consisted of my mother, my sister, and me, and we moved a number of times, maybe three or four times in my earlier childhood. Cincinnati was very community-oriented, so each community had a different “flavor.”

Since you mentioned your mother, did she have a more significant influence on your art or just on your life in general?

Espy: Mom played a huge role; like any parent, she had her own challenges and flaws. What I remember about Mom, and what anyone remembers, is that she was very kind and loving to anybody she came across. She would get mad at her kids sometimes when we acted badly, but Mom’s influence was definitely that of a woman who taught her kids that she loved us and that we could do anything.

Espy: When she [his mom] was admitted to the nursing home, she called me and said, “I have something for you.” I didn’t know what it was, so she handed me this bag and said, “Open it up.” As soon as it came out, I was like, “Wait, what? You still have this?” She kept it in her nightstand—my whole life. When she gave it to me, she said, “I know you’re going to be a famous artist.” That was easily 10 years before I ever started doing art full-time.

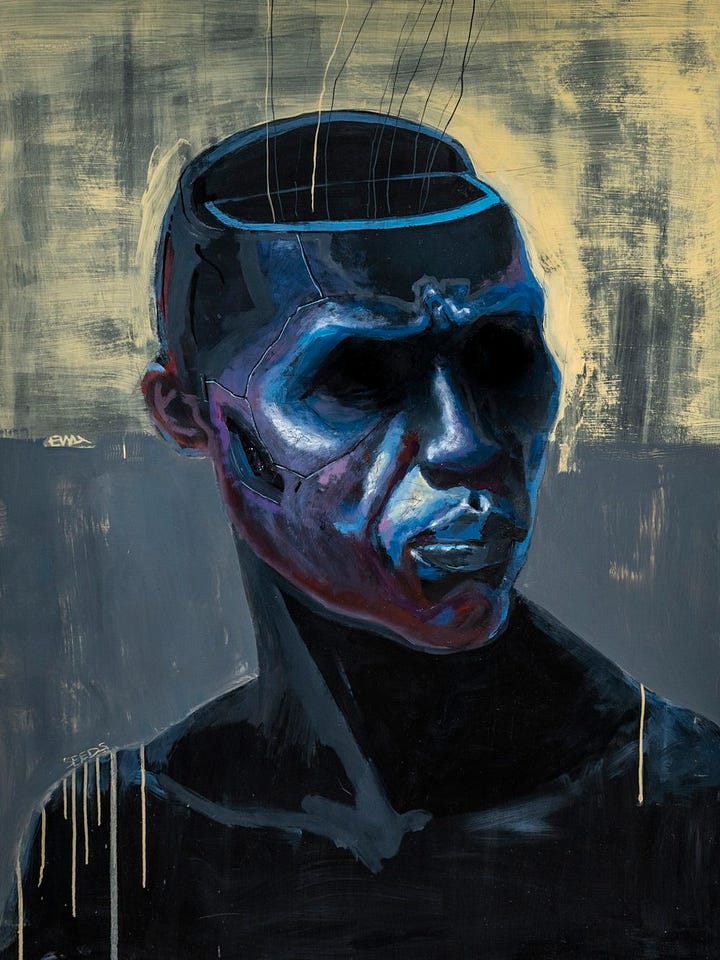

What were the first steps in your creative process when developing the “Up From The Asphalt” collection?

Espy: “Up From The Asphalt” was different because there was no planning or forethought in it because it was never conceived. What happened was an innocent man, or a man who didn’t deserve to die on the concrete, was killed in front of the whole world on live camera. We witnessed the kind of brutality that occurs in U.S. law enforcement. In a lot of various ways, it was exposed in a way I had never seen before. That created a lot of anxiety and a lot of helplessness inside of me. Eventually, I had to put it somewhere. When I eventually decided to [start painting], with the help of my wife’s encouragement, I just started putting paint on canvas. It eventually started depicting scenes specifically from that crime scene. I painted the George Floyd arrest and killing depictions within the first ten days of the incident. However, it was COVID at that time, and the place where my studio was located had to close its doors due to COVID restrictions.

So those Floyd pieces had to go in storage. They lived in storage for three years until last February, when I brought them here to Connecticut. Before those pieces were even completed, they went into storage. A good part of the exhibition you saw were works that were never meant to be shown and were never completed, but I showed them in the last state that they were [in] when the studio had to close its doors.

Imagine you were someone with no background in the arts, specifically a white person, and you went to view the “Up From The Asphalt” collection. How do you think you would perceive it? What do you think would be the most significant takeaways?

Espy: I don’t know if I have ever imagined myself seeing my art from a white perspective. First of all, I can think about what I hope it will look like. I would hope that it would be inviting. That seeing it would make you want to get closer to it, make you want to spend some time with it. With any of my portraits, I hope people can find themselves somewhere. Even if it’s a white person, I hope there’s a commonness in our humanity that even though they might not identify with being Black, they might identify with being an innocent kid. Or they might identify as being a kid who decided to express themselves one day by wearing their afro out. Maybe they’ll think about when there was a time “I decided to express myself.”

Back to your creative process, what emotions go through your head? What do you feel is the central inspiration, “the power?” What’s the gasoline that gets your car moving?

Espy: The motivation changes with what happens to be going on either with me or societally. But the process is, say, I experienced something in society or my personal life that [makes me go] “Man, I want to communicate that” or “I want to share that thing.” Then, the process is that you first have to capture pupils—the image has to capture attention, and then after it has captured your attention, it has to continue to speak. If you see it, it can walk away, and then it was just a “flash.” But if you see it and then you want to get closer to it, and then you want to stand in front of it for a while, that means the art has more to say. For me, the more to say is in the brushstrokes, color choices, and what the composition or arrangement does. Some arrangements point you in a direction, some cause you to be still, and some invite you to look further. I take all that into consideration. I have to admit, though, that sometimes, with a painting, those ideas and thoughts are there at the start: the color, the composition, and the movement. Sometimes, it’s like walking into a kitchen hungry and making something delicious out of what happens to be there, making it up as you go. The more often you “cook,” the better you get at making something good out of whatever. I’ve been “cooking” for a while, so sometimes I can walk in the “kitchen” and slam something together that’s “delicious” that I never made before—a little humble brag.

You were saying emotion plays a big part in the creative process. Let’s say you were advising all the creatives out there; if they were to ask you what plays the biggest part in creating a piece that they want to hit. Is it logic and intellectualism, or is it emotion—pure emotion? What should they hone in on?

Espy: All of us are geared in one direction or the other. Some of us lead first with our brain, and our heart trails somewhere behind; some of us lead with our heart, and then our brain trails behind. From my perspective and my experience, I like to lead with emotion. If a tiger jumps out of the woods, your logic goes out the window. The first thing you feel is emotion. The first compelling thing is emotion, and then if you can elicit the emotion that captures someone now, you have their attention long enough to engage their brain. If the art captures your emotion and you come closer, I always try to give you a few more treasures to ponder, think about, and question. I hope people have the experience of “Oh wow, this is emotionally engaging, but he also made me think.”

Can the use of AI properly convey emotion?

Espy: It’s easy to be charming the first time: flowers, roses, candy, or candles. There are a lot of things to be romantic about at the beginning. But if that’s all you got, then it flickers out. AI lets you have an instant romantic infatuation, but I don’t believe AI will have the capacity to go as deep as the human spirit. Although I believe it’s getting more and more sophisticated, I can’t imagine anything being more sophisticated than the nuances that exist in flesh and blood. AI can reflect heartbreak, but it can’t know heartbreak. AI can reflect joy as a reflection of what we input, but it can’t experience the surge of chemicals that happens in our bodies when we feel euphoria, bliss, heartbreak, or outrage. You can’t put that in an “X on, O’s off.” You can’t do that.

Throughout your life, what influenced you more: your perspective as a Black man in America, your perspective as a Christian, your perspective as a god-following man, or your perspective as an artist?

Espy: It’s hard to extrapolate any of those things because the older I get, the more I realize I live in all those things all at the same time. Definitely, being a follower of Christ has a huge influence on my work, first and foremost. Still, I’m learning that I’m not just a Christian, I’m not just a Christian who’s an artist, I’m not just a Christian who’s a Black married man who’s an artist, I’m all those things at once, and the more I integrate all those things, the more authentic my work is.

Espy: So, if I tried to be a Christian and not be a Black man, I wouldn’t like where that would lead my art, but if I tried to be an artist and just a Black man and ignored my faith, I wouldn’t like that either. I’m trying to take all of who God made me. I see myself in a way everyone I think should. I am a particular instrument with a particular set of functionalities, and I want all of those functions to work in service to God. My instrument is uniquely different from every other individual on the planet, as everyone is.

During the time after Floyd’s murder, I felt outraged at God. It wasn’t really because of the murder. More specifically, it was seeing white America’s reaction to the murder that influenced my feelings of outrage toward God. Did you feel anything the same?

Espy: I definitely felt outraged towards the complicity of white America and, I should say, also the complacency of white Christians. I don’t recall feeling an outrage towards God, but I definitely think some of the helplessness I felt at that time was trying to live within the social construct of the church that suggested that protest isn’t “Christian business” or that a march isn’t the “business of a disciple” that it was “civilian affairs” because we are “not of this world.” I have since changed that philosophy in dramatic ways, according to the scriptures: “Love the lord, your god, with all your heart, soul, mind, and strength, and love your neighbor as yourself.”

Espy: Those are pinnacle—there is no way I can say “I love god” and stand quietly while men and woman, brothers and sisters, I don’t care if they’re Black or White, Gay or Trans—when people are being oppressed and abused, God is not pleased with that and nor should I be.

Let’s say God granted you one painting, which would instantly change the world with God’s power. What is the first thing that comes to mind when considering what you would paint?

Espy: Yeah, I thought about that. It’s a lot of pressure for one painting, but if God’s going to take that painting and change the world, if there was a way to represent humanity in one face, I don’t know how that’s possible, but if I could paint one face that depicted how God feels about us as people, I would try and paint that. Maybe I would paint my mother again.

On those faces, if you painted one face, what do you think the primary emotions would be?

Espy: As I think about it, it would definitely be my mother. The emotion her face would convey would be kindness and love for sure. I ain’t trying to be sappy. That’s the legit answer.

How did academia influence you?

Espy: I enrolled in a program that was called Visual Communication. That was the business side of art, learning how the printing process works, how a concept becomes a layout for a magazine cover, [how that] becomes the blueprint for a magazine cover, [then] becomes the printed cover that gets bound together and published. I learned typography, illustration, design, and painting. I’m a painter today because my high school art instructor, the illustrious Franklin McKenzie Shands, taught me techniques for rendering and portraits. I use the exact same thing he taught me when I was in high school. His teaching gave me a leg up on my classmates in art school, but Henry Koerner was the painting teacher who had the biggest influence on me. A lot of my painting styles are a reflection of his color choices and his brush marks.

I ask you to not be humble here. What do you think is your most underrated skill? When people critique, look at, or review your art, what is one thing that you think they don’t bring up enough, something that you wish would be given more praise, or something that makes you think, “I’m pretty good at this, this should be brought up more.”

Espy: Since you gave me license to brag, I’m good at a lot of things, and to the person who loves art but doesn’t necessarily know a lot about art, I appreciate their feedback. They see something, they love it, or they don’t love it. When other artists appreciate something that’s more nuanced, they can call out that. Maybe someone who doesn’t practice art wouldn’t recognize [it]. I especially appreciate that. I will say this, though: it is not uncommon for a professional artist to use tools that I, being a purist, might call shortcuts, like using a projector to capture a figure or a cityscape on a canvas. When it’s fine art, for the type of art I do, I prefer to fight and wrestle with the figure all day until I get the figure right rather than take 10 minutes to trace an outline. I love the fact that if I were trapped on a desert island and I didn’t have any oil paints or any brushes, I could take a rock and go to the side of a cliff and carve images raw and without any assistance. Humble brag.

Have you ever seen an elephant or a monkey paint? When it comes to animals creating art, do you think an animal could ever think about making art the same way we do? Could an animal produce something on the same level as a human?

Espy: I’ve seen videos of an elephant with a paintbrush in its trunk painting a beach scene. I imagine a trainer could train a particular animal with a certain skill set to follow a course of steps that leads to an outcome that looks like a beach. I’ve also seen animals given a brush, and they randomly select colors, and they randomly make marks. They do what you would consider abstract expressionism, so I can never say what was in the mind of an animal. But I’ll sum it up this way.

Espy: Our heavenly father was the first creative; he spoke and created the world and made us in his image, so I know at least we, as humans, are creative. On occasions in nature, whether it’s a songbird in the morning, dolphins with their clicks, a dog jumping, or a horse prancing and doing different things. Creative expression does exist in wildlife. Maybe it comes out in the way a bird builds their nest. I don’t want to limit the ability of animals to create art. I’m not going to ever spend thousands of dollars on an elephant painting.

Here’s a fun one. If you had infinite time to instruct an animal to learn how to paint in a one-on-one class, what animal would it be?

Espy: It had to be one most like me. I’m thinking it's probably something in the primate family. That is going to move most like I do.

Out of every event in the Bible, which would you rather paint in person?

Espy: I would want to capture Moses’s glowing face when he came down from Mount Sinai after spending time with God. His face, he would cover it. He didn’t want people to see the glow fading away. I would want to try and capture his face while it was glowing. I might have to paint that one.

Out of these three groups, who would you much rather paint with? The 12 Disciples, Job, or Abraham?

Espy: I’d say my tendency is to lean toward Job.

Job? Why Job?

Espy: There’s something about suffering that, if you capture it in a thoughtful, compassionate way, it draws people in. I don’t know if I mean suffering, but for someone like Job, who is going through something difficult, there would be a lot on his face to paint. There’s nothing more boring than painting a beautiful, happy person for me. I shouldn’t say [that]. I paint beautiful people. What I mean is a face that is culturally of that aesthetic—that is easy to look at in the first place.

Eurocentric features?

Espy: Yeah, or even if it’s not. Even if it’s more Black-and-Brown culture. When the face is super polished—in that face—it’s hard to find something compelling. Although, that’s probably a fault of mine and not necessarily of the individual. A person with a pretty face can be just as complex, but there’s something when someone has wrinkles. When they wear life on their face, there’s more substance to me.

Do you consider all things called “art” to be on the same level?

Espy: No, and here’s where I’m going to be an art snob. Everyone has the right to take a piece of clay, pigments, or paints. They can use their hands, they can use brushes, they can use stones. Whatever they use and [they] express themselves, I’ll call it art, right? I think one of your questions was, “How do I define art?”

Yeah, I was just about to get to that. Often, I think the word “art” is too broad. I feel as though we need different terms to describe the various levels. I think back to ancient Greek society’s six different terms for love, such as you don’t love your wife in the same way you love your friends. So, what should your art’s definition be?

Espy: I stole this from something I heard in the last month or so, but “creativity for the purpose of creativity that exposes something inside of you is art.” Does that make sense? Creativity for the purpose of making money could be art, but now it’s just a commodity. Creativity for problem-solving is good, too. I started by saying I don’t think that all things that we call art is art [but] I should better quantify it as: art does have relative value. It’s hard for one individual to assign that value. I will give you this, and then you will have to let it go.

Espy: Any fool can dip his hand into a bucket of paint and throw it against the canvas with his hands and just splatter. The guy who did it first did something creative. The rest, they haven’t done anything new. Putting your hands in the bucket, slinging it around, or tying a boot to a string, covering it with paint, and then swinging it around. Maybe you can call that art the first time you do it—the first time it’s done—or if you practice it to develop a unique technique. When it ceased to be unique, it ceased to have the same creative value. I’ll still call it art, but I don’t value all art the same, just like I don’t value all music the same way.

If you could take all your skills from painting and transfer them to another “sector” of art, which would it be?

Espy: It would be music. In the work that I do, I work with a lot of different mediums. I work with oils, acrylics, and watercolors. I use brushes, scrapers, spatulas, all that stuff. [I] haven’t done it in a few decades, but when it’s time to do sculpture, I believe I will be able to pick that up again. Musically, I would want to be like Prince. I would play the bass, the lead guitar, the percussion, and I would want to produce it all.

What does your professional art career look like?

Espy: It’s interesting right now. A year and a half ago, I was an artist with an art studio who produced art in albums, and then I sought venues to play my album for a month or 3 months at a time. I sell art. A year ago, I acquired this space, and now I have a studio and a gallery. I’m an artist upstairs; I’m a businessman down here. I’m thinking about marketing, I’m thinking about cash flow, I’m thinking about budgets, and I’m thinking about market saturation. I’m interested in local commerce. Things I don’t think about upstairs, [I] definitely think about down here. The reason it’s a Saturday afternoon in January [and] my front door is locked is because there is not sufficient walk-in commerce for me to have my doors open. For people to see my artwork, I’ve become an event planner. I have events here, galas, and a Valentine’s Day celebration coming up, so I get potential buyers here celebrating some occasion in the presence of all my art—an opportunity to sell. I have a lot of different roles right now.

Have you heard of the “12 Steps on the Graphic Designer’s Road to Hell”? It is by Milton Glasier; essentially, it describes various ways a graphic designer can sacrifice their ethical beliefs for a “check.” I am bringing this up because I would like to ask what you believe are the 12 steps on a Fine artist’s way to hell, more specifically, an artist from a marginalized group. What are some steps?

Espy: I want to celebrate Black people. But like what you mentioned, I don’t want to sell food just because people will eat it. So, if I was selling food, man, I want it to be good, nutritious, healthy, thoughtful, clean, [and] beautiful presentation. When you leave, it’s good for your body, right? I want to sell that. I don’t want to give you deep-fried, cholesterol-filled sustenance as my mainstay because I know you’ll eat it. Traditionally—as Black artists paint Black women—there was a period of time when Black people, in general, were not celebrated in our culture, right? There wasn’t a space for Black people to celebrate us, and we weren’t celebrated anywhere else. The depictions of us before we could own it ourselves were stereotypical and degrading. At some point, we painted—especially in the 70s as we felt more empowered—depictions of the Black family. A strong, muscle-bound, dark-skinned Black man reaching down and grabbing the arm of his curvaceous, big bosom, big behind—I don’t mean that in a bad way—Black woman, lifting her up.

Espy: I think there was a time when our culture needed those images. We’re strong, we’re healthy. She’s very curvaceous and eating well. We’re prosperous. [We see] A continuation of that same thing, but just because we buy it doesn’t make it good food anymore, so let’s celebrate our body types, but let’s not paint big behinds because people like buying big behinds. You know what I’m saying? I’m in a little bit of a financial fix right now that a few sales would get me out of. If I wanted to have instance, if I wanted to sell stuff, I could just paint a bunch of naked girls, and I’d be fine. People buy that junk all day long. I’m not painting nudity for the sake of nudity. I’m not painting flesh to celebrate flesh. If I ever did do something that included some aspect of nudity, it would be for a greater message than just flesh. That would be my fast track to even just an emotional hell or purgatory of feeling like I got to sell this.

Do you have a motto you live by, something that you tell yourself to get through moments of turmoil?

Espy: Something that comes up with the art is the way that I paint. I had about 28 years after art school, where I wasn’t professionally doing art. To stay active, I was always searching for the most beautiful marks I could make. I was sketching anywhere I was. I would always be sketching if I had a ballpoint pen and copier paper. I would always find creative ways to make beautiful marks. Twenty-eight years of trying to find beautiful marks has made me a better painter. The paintings I do today are just an assemblage of [many] individual marks. You can’t make a masterpiece without making daily marks that are beautiful. Those marks, for me, translate into how you treat people. If you’re kind to the clerk, you’re kind to the hostess or kind to hold the door—How you treat people on a daily basis.

If you had to symbolize your life so far in one color, of course, not skin color, but what color would it be and why?

Espy: My daughter used to ask me what my favorite color was. It’s going to sound cliché. I used to say my favorite color is black. Not because I’m a Black man—technically, I’m an artist, so I’m not black. I’m brown. My favorite color is black because I learned in high school that when I paint, I save the black until last, or I save black till near the end. Black transforms everything else. When the black goes on, [for example] black next to red, it completely changes it. It adds contrast to everything. No matter where you put the black, it has a big impact. That’s what I like about black.

He then showed me an unreleased collection of a completely different genre. This exhibition would have been called “Genesis,” but Espy decided to change it. We could not use the camera after this point, but luckily, he explained why he chose to change the name before we stopped filming.

Espy: On the seventh day, God rested, right? Did God rest because he was exhausted? The almighty, all-powerful, omnipotent God got tired? I don’t think he needed to take a nap—or he sprained his ankle. He didn’t rest because he was tired. At some point, we can say, “That’s good enough. This is beautiful, this is good. I could keep going, but I am content.” He is teaching us that we can be content. I started this exhibition with a goal in mind, and [when] I started painting towards this goal, I started stressing out about the art for an exhibition about being content. Then I realized, “Oh, wait a minute, as I do this work, I’ve got to be content with what God gives me, at the pace he gives it to me, and not feel stressed about keep going, keep going, keep going, when God himself rested.” So, an exhibition about Genesis and resting reminded me that I needed to rest.